Eggs

Background

The unfertilized egg is considered an important and inexpensive food source, particularly high in protein, including 0.21 oz (6 g) of complete protein per two-ounce egg. However, it also includes 0.42 oz (12 g) fat, both saturated and unsaturated, which is nearly all located in the yolk. Therefore, if the yolk is separated from the albumen (white) of the egg and the white only used, the egg contains no fat and a fair amount of protein. The egg also contains significant amounts of iron, vitamins A and D, riboflavin, and thiamine. However, that nutritional value does vary somewhat depending on the diet of the laying hen. Annual consumption during the late 1990s averaged 245 eggs for each of the 265 million people in the United States.

While geese, squab, ducks, and turkeys supply edible eggs, the preponderance of eggs eaten come from domesticated chickens bred for laying eggs. The females (mature hens and younger pullets) are raised for meat and egg production and breeds have been developed to fulfill commercial needs. Each of the 235 million laying hens in the United States produces about 300 eggs a year. Farmers are careful to house and feed the chickens to maximize laying and ensure the hen has a relatively long and healthy life. Egg producers also have flocks of hens at different ages, ensuring they have a steady supply of eggs ready for market to provide year-round income.

Eggs are an important ingredient in many recipes. Because the protein in the egg white coagulates as it is heated, eggs are utilized in many recipes as a structural component. Stiffly-beaten egg whites expand as they are heated and are used as leavening in angel-food cakes, souffles, and meringues. In cake batters that utilize the entire egg, the egg acts as leavening as well as providing moisture and firm texture. Soups and sauces use eggs as a thickening agent. Ice creams often include eggs to prevent the formation of ice crystals which can ruin the product. But the plain egg is eaten by millions each day for its own unique flavor and nutritive value—they may be boiled, poached, fried, scrambled, or baked.

Fresh egg production is primary to the egg industry, however, a significant amount of egg production includes eggs purposely broken and used for powdered eggs, frozen eggs, or purchased by food producers for inclusion in food products. (In some fresh egg production plants, accidentally broken eggs are sold to bakeries or other food production plants.)

History

The egg has been a protein source for centuries. Sometime in the second millennium B.C. Indian wild red jungle fowl, the ancestor of the modern chicken (Gallus gallus) was dispersed throughout Europe, China, and the Middle East. Chickens were brought to the New World on Columbus's second voyage in the late fifteenth century. These imported chickens laid eggs year-round and were considered most valuable for their egg production rather than for meat. Soon family farms raised chickens for the family's consumption of eggs and meat within the household—few families had laying flocks of any size. However, by 1800 chickens began being raised for meat and egg production in increasing numbers in the United States. Until World War II, egg production came from rather small flocks of less than 400 laying hens. After the war, automation and advances in breeding, feeding, and developing efficient henhouses gave rise to modern high-volume chicken farms. Today, a single egg producer may well have a flock of over 100,000 laying hens—and some have flocks of over one million.

Raw Materials

The egg itself is the ingredient in egg production. Soaps are used in egg production facilities to clean the shell. Some processors coat the shell in a light film of oil.

However, the hen from which the egg drops can be considered an important part of the raw material. Certain breeds lay the majority of eggs in the United States. A particularly prolific laying hen is the Single Comb White Leghorn. This breed reaches maturity early and can begin laying at 19 weeks of age and continue to lay eggs for about a year. In addition, the Leghorn utilizes feed efficiently, is fairly small, can adapt to a variety of climates and is able to lay a relatively large amount of white eggs, the type most in demand. Plymouth Rock hens, Rhode Island Reds and New Hampshire hens produce brown eggs much favored in New England.

Feed for chickens is generally all-mash, consisting of sorghum grains, corn, and either cottonseed meal or soybean oil depending on availability. Farmers carefully mix the mash so that the chickens get just the right amounts of protein, fat, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. This is essential in that the nutritional quality of the laid egg depends on the feed the chicken was given. All additives to chicken feed must be approved by the federal government (after research on toxicity to animals and humans is determined). Hormones are not given to chickens, but they occasionally require antibiotics. On average, a chicken requires about 4 lb (1.8 kg) of feed to produce a dozen eggs; a Leghorn hen eats about 0.25 lb (0.1134 kg) of chick mash a day.

Processing Eggs

Some egg farmers have their own egg processing facility on premises. Others contract with egg processing firms in the locale who purchases eggs and processes them. Generally, an egg moves from the egg farm to being ready for public consumption in just a few days.

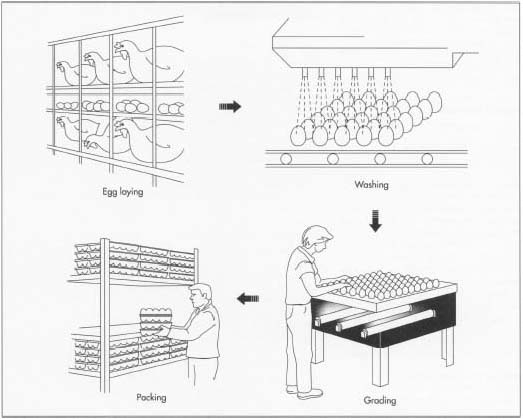

Laying the eggs

- 1 Hens are kept in cages, usually in groups of three to five. After the egg is laid, the cage is devised so the egg rolls out for easy collection. Eggs are gathered twice a day, generally by automated machinery but are occasionally still gathered by hand. Eggs are gathered as soon as hens lay them because warmer temperatures encourage physical and chemical changes that affect freshness adversely. Thus, many egg farmers refrigerate the eggs immediately after gathering before they are packed for transport to the processor.

Packing the eggs on the farm

- 2 The eggs are then packed on skids that are formed of layers of flats—eggs are packed on flats that include 2.5 dozen eggs, with as many as six flats per layer (layers of six flats are separated by a board). A single skid holds about 30 cases or 900 dozen eggs. These eggs are then sent to the processing plant via truck.

Washing the eggs

- 3 The skids are brought into the production room and the individual flats are put on the conveyor, one at a time. Individual eggs are grasped by small suction cups and placed onto another conveyor belt. Now, the eggs are moved into the grader where they are cleaned with a USDA approved cleanser. They are rotated as brushes and water jets move carefully across the eggs. A fan then dries the eggs.

Candling and grading

-

4 The cleaned eggs are graded in a candling booth which is a dark

cubical or room. A penetrating light is shined on the eggs in order to

grade them. The egg processor is able to grade the egg during candling.

The trained candler can see that an older egg has thinner albumen; thus,

the yolk casts a sharp shadow and immediately indicates an older egg.

Eggs are graded as "A" (sold for household use or at

retail markets), grade "B" (used mostly for bakery

operations), or grade "C" (sent to egg breakers who break

the shell in order to convert it to other egg products);

higher grade eggs have a thick, upstanding albumen, an oval yolk, and a clean, smooth, unbroken shell. Eggs with cracks that are not leaking are removed from the process at this point and are not packaged for household use or retail sale.

Commercial egg processing is a quick business that relies on speed to market in order to provide fresh, quality product. Hens are kept in cages that are devised so that when an egg is laid it rolls into a collection bin. The eggs are then packed on skids which are formed of layers of flats. Skids are individually placed on a conveyor belt. Each egg in the skid is grasped by a small suction cup and placed onto another conveyor belt. The eggs move into the grader where they are cleaned with a USDA approved cleanser. They are rotated as brushes and water jets move carefully across the eggs. A fan then dries the eggs. Once graded, the eggs are placed in cartons, packaged, and shipped to stores.

Commercial egg processing is a quick business that relies on speed to market in order to provide fresh, quality product. Hens are kept in cages that are devised so that when an egg is laid it rolls into a collection bin. The eggs are then packed on skids which are formed of layers of flats. Skids are individually placed on a conveyor belt. Each egg in the skid is grasped by a small suction cup and placed onto another conveyor belt. The eggs move into the grader where they are cleaned with a USDA approved cleanser. They are rotated as brushes and water jets move carefully across the eggs. A fan then dries the eggs. Once graded, the eggs are placed in cartons, packaged, and shipped to stores.

Weighing and packing the eggs

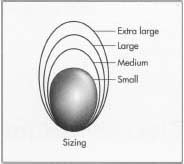

- 5 The grading process actually includes the weighing of the eggs as well. At the grading station, a machine weighs each individual egg and remembers what each egg weighs. In the United States, eggs are sized (extra large, large, medium, small) on the basis of a minimum weight rather than by size of egg. Extra large eggs must weigh a minimum of 2.24 oz (64 g), large at least 1.96 oz (56 g), medium at least 1.72 oz (49 g), and small at least 1.47 oz (42 g). The packing machine then assembles cartons based on the weight of individual eggs; thus, the heaviest eggs are "found" and packed into the extra large cartons, the next heaviest tier are packed in to the large-size egg carton, etc. Packaging varies, but is generally either recycled cardboard or a colored polystyrene the egg producers purchase from a packaging manufacturer.

Transportation to trucks

- 6 After packing, the cartons are placed on a conveyor and packed into flats by machine, put into trucks (generally refrigerated) and sent to be sold. One large Pennsylvania egg processing plant processes 45,000 dozen eggs per day.

Quality Control

Quality control happens in all parts of the egg processing. First and foremost, the chicken farmer ensures that his hens are well fed with a diet specifically formulated to provide the best grade of egg. Shell strength, for example is determined by the presence of adequate amounts of vitamin D, calcium, and other minerals in the chick mash. Too little vitamin A can result in blood spots (not harmful to the consumer but render an egg undesirable and unusable to the consumer). Laying hens also require a good supply of clean fresh water. The henhouse is well insulated so that the farmer can control the temperature. Facilities are windowless so that light can be manipulated—egg production is spurred by maintaining a lighted environment 14-17 hours a day. The henhouse should be comfortable for the hens and well-ventilated. Birds are generally kept in cages because they are easier to clean and it is easier to collect eggs from cages; however, some hens are allowed to roam free.

Effective candling is essential to quality control as well. Candling reveals nearly everything that is need to know about the quality of the eggs—age, cracks, clarity (no blood spots). Furthermore, most egg processors can tell much about the quality of the egg just by looking at the shape and color of the shell.

Salmonella is a hazard of the egg industry. However, it is estimated that 90% of eggs are free from salmonella at the time they are laid. Salmonella bacteria occurs after laying. Proper washing and sanitizing of eggs with a government-approved soap eliminates most Salmonella and spoilage organisms that are deposited on the shell from the hen ovaries.

Egg farmers are also careful to refrigerate the eggs as soon as they are gathered just prior to packing. The egg processors, too, move eggs quickly through the processing to packaging to ensure the eggs are clean and fresh for the consumer.

Furthermore, government standards for the grade and size of eggs are strictly adhered to. Flocks are periodically monitored for proper feeding as well as acceptable facility standards.

Byproducts/Waste

Eggs with cracks are removed from the egg processing line. Broken eggs are thrown into a bin and sold for utilization in dog food. Eggs that have cracks but are not leaking are taken away for pasteurization and transformation into liquid egg products (sold in cartons of plastic containers or perhaps even frozen). They may be sold to another processor who transforms them into powdered eggs, or they may be sold to local bakeries for use in goods there. Many egg processors are aware of the ecological problems created by the polystyrene cartons and egg processor encourage recycling of the product packaging.

Where to Learn More

Periodicals

Wexler, Mark. "Eggsquisite!" World Magazine (March 1989): 70.

Other

American Egg Board. http://www.aeb.org/ (June 29,1999).

Manitoba Egg Producers. http://www.mbegg.mb.ca/ (June 29, 1999).

— Nancy EV Bryk

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: